C'est bon de vous avoir ici !

Notre boutique utilise des cookies. En cliquant sur Accepter, vous acceptez nos conditions d'utilisation et notre politique de confidentialité.

SKU:

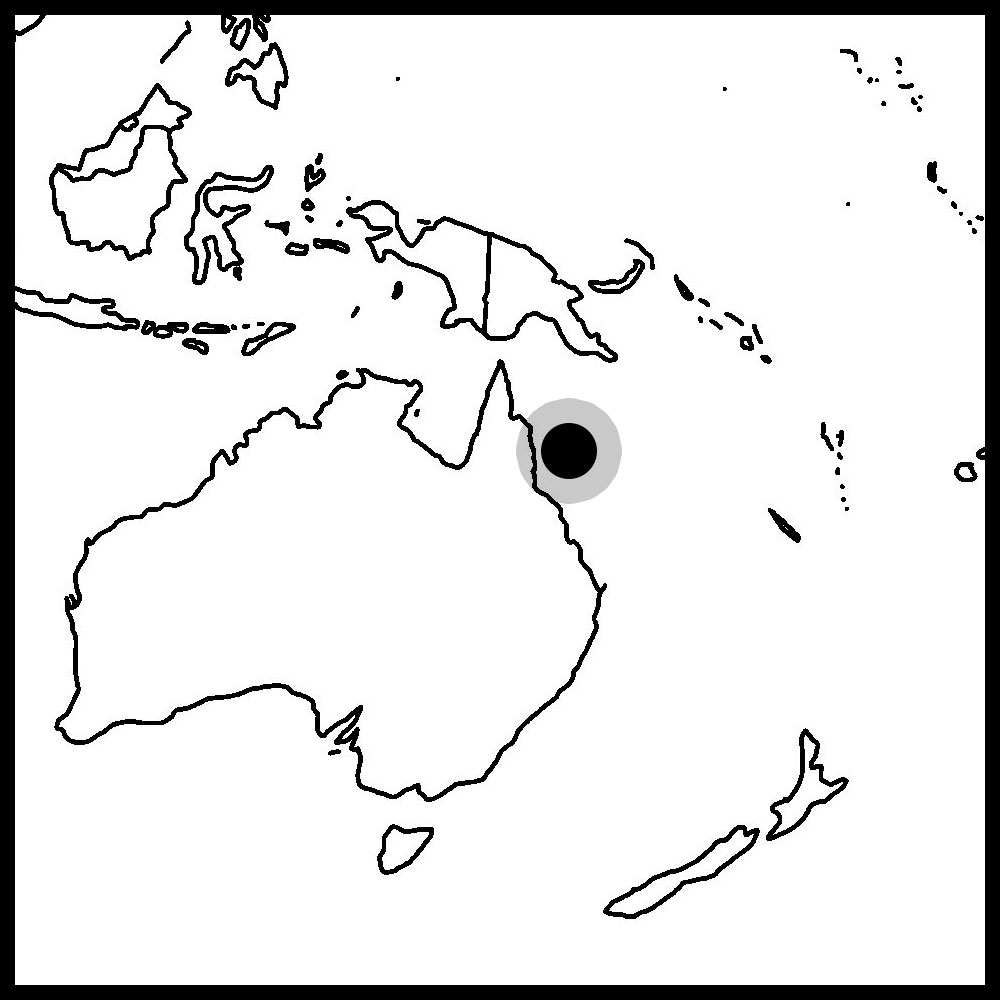

Rhodactis are found in the islands of the Indo-Pacific including Fiji, Tonga, Solomon Islands, and the Great Barrier Reef.

Let’s tackle lighting first. Rhodactis can be kept in brightly lit tanks like you see here in my friend Nathan’s tank. It’s an SPS dominated tank with the mushrooms about 18-20” down in the water column. If I had to guess, they are in roughly 100 to 150 PAR.

Alternatively, we have kept them in lower light of around 75 PAR and they have been fine. Rhodactis have more or less consistent coloration so switching between lighting technologies like LED vs T5 or ramping up intensities doesn’t really change their appearance much. So long as you are providing the requisite lighting intensity and not burning them, you should be successful keeping them.

As for flow, you’re going to want to keep it really really low, no exceptions, end of story. There is two main reasons for this.

The first reason is, one of the few ways that mushrooms meet an early demise is if they detach from the substrate they were holding on to and drift around the tank. For whatever reason, Rodactis are not great at reattaching themselves to anything and too much flow will make it almost impossible for them to do so.

The second reason is that they extend out more in areas of low flow. So in general, lower flow means a happier coral.

When it comes to nutrition, just providing light for photosynthesis is adequate, but it is possible to spot feed them if you shut off the pumps and are patient.

As I mentioned before, the Rhodactis genus is highly diverse and as such, there are going to be some Rhodactis mushrooms that are more aggressive feeders than others. Is it worth it to feed them? I’m not really sure. I’ll let you decide.

Name: Rhodactis Temperature: 24-26C Flow: Low Flow PAR: 50-150 Water parameters: Nitrate 5-20 mg/l, Phosphate 0,05-0,15 mg/l Feeding: No feeding required, but may be fed plankton (e.g. Goldpods) if desired Care level: Easy/Moderated Location Rhodactis are found in the islands of the Indo-Pacific including Fiji, Tonga, Solomon Islands, and the Great Barrier Reef. Lighting Let’s tackle lighting first. Rhodactis can be kept in brightly lit tanks like you see here in my friend Nathan’s tank. It’s an SPS dominated tank with the mushrooms about 18-20” down in the water column. If I had to guess, they are in roughly 100 to 150 PAR. Alternatively, we have kept them in lower light of around 75 PAR and they have been fine. Rhodactis have more or less consistent coloration so switching between lighting technologies like LED vs T5 or ramping up intensities doesn’t really change their appearance much. So long as you are providing the requisite lighting intensity and not burning them, you should be successful keeping them. Water Flow As for flow, you’re going to want to keep it really really low, no exceptions, end of story. There is two main reasons for this. The first reason is, one of the few ways that mushrooms meet an early demise is if they detach from the substrate they were holding on to and drift around the tank. For whatever reason, Rodactis are not great at reattaching themselves to anything and too much flow will make it almost impossible for them to do so. The second reason is that they extend out more in areas of low flow. So in general, lower flow means a happier coral. Feeding When it comes to nutrition, just providing light for photosynthesis is adequate, but it is possible to spot feed them if you shut off the pumps and are patient. As I mentioned before, the Rhodactis genus is highly diverse and as such, there are going to be some Rhodactis mushrooms that are more aggressive feeders than others. Is it worth it to feed them? I’m not really sure. I’ll let you decide.

€299,00€179,00

SKU:

Name: Goniopora sp.

Temperature: 24-26C

Flow: low-mid

PAR: 75-150

Water parameters: Nitrate 5-20 mg/l, Phosphate 0,05-0,15 mg/l

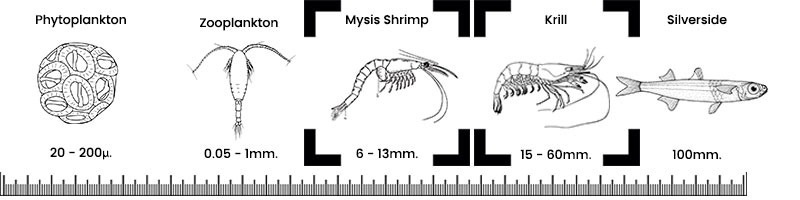

Feeding: They are adept feeders that can grab and consume a wide variety of foods ranging from coral-formulated sinking pellets to frozen food such as brine shrimp, mysis, and krill.

Care level: Moderade

Part of the reason for the recent success is sourcing the coral. There are around 20 different species of Goniopora and some are more hardy than others. We have had the best success with Goniopora that originated in Australia. They tend to have better coloration and smaller polyps than the ones I�ve seen come from other geographies like Indonesia.

Goniopora are a photosynthetic coral so they derive some of their nutritional requirements from light. This is done through a symbiotic relationship with dinoflagellates called zooxanthellae that live in the flesh of the coral. The dinoflagellates are actually the photosynthetic organism and the Goniopora colony derives nutrients off of the byproducts of the dinoflagellates� photosynthetic process. Zooxanthellae is usually brown in color and the coral tightly regulates the population living in its flesh. Too little light will cause the coral to turn brown in color. As it seeks more nutrition, the coral allows more zooxanthellae to build up in its flesh. Usually a coral will prefer a specific range of lighting intensity but that is less of the case with Goniopora.

Goniopora can thrive in a wide range of lighting. We have kept Goniopora in different lighting intensities here at Wild Corals_ranging from very dimly lit 50 PAR tanks all the way to bright aquariums receiving over 200 PAR. I would recommend placing them under moderate lighting intensities, between 75-125 PAR. Goniopora are consistent in their appearance under different lighting. That is to say that a red colored Goniopora won�t suddenly turn green when moved to another aquarium with slightly different lights above it. Sounds strange, but there are plenty of corals out there that can shift their color palate like that.

Having said that, the type of lighting system chosen will have a dramatic effect on how they are displayed. There are some incredibly fluorescent varieties of Goniopora that glow like safety cones under the right blend of actinic lights which would not be apparent at all under daylight lighting.

One of my favorite things about Goniopora is how the tentacles sway in the current. It is one of the most dramatic and aesthetically pleasing large polyp stony corals as far as motion is concerned. It�s movement is almost hypnotic and is one of the things that makes Goniopora such a great focal point in the aquarium.

One mistake I think some reef keepers make is providing them too much flow. If you have a powerhead blowing right at Goniopora from short range, it may kill off some of the tissue at that point of contact and cause a chain reaction to the rest of the colony.

Goniopora appreciate low to medium flow, but preferably with some randomness to it. That way you will get that gentle waving motion which helps keep the coral clean and brings food past the colony. If you see the tentacles violently thrashing about, that is probably too much flow and it would benefit from being relocated to a more calm section of the tank.

Perhaps the biggest difference between the time when aquarists struggled keeping Goniopora to now is the change in mentality regarding coral feeding. For decades the majority of hobbyists believed that feeding was not necessary. Fast forward to today and well€ the majority probably still don�t But_at least now there are more resources available demonstrating the positive benefits of feeding as well as a variety of coral foods in both powder and liquid form on the market.

I am absolutely convinced that Goniopora have to be fed and fed a lot. I�ve kept a lot of different types of Goniopora and just a personal anecdote, the times I�ve struggled with them had to do with neglect and lack of feeding. When I diligently provided them with a high quality food source, they almost always thrived.

What to feed Goniopora is a good question. Goniopora do not put on dramatic feeding displays like some large polyp stony corals. In fact, they seem to shy away from contact rather than aggressively trying to capture food. They have this Ðpogo hopperÓ motion to their polyps when food is introduced. Some believe that the coral takes in a lot of their nutrients through their skin more so than consuming it with their mouth, so even if you don�t see it actively feeding trust that something positive is still happening.

There are two types of food that I like to provide Goniopora. The first is liquid amino acids. In short, they are simple organic compounds that play a major role in building proteins as well as other biological functions at the cellular level. Corals regularly take in available amino acids from the water column so it is easy to provide them with adequate quantities by broadcast feeding an amino acid solution. If you want to know more about amino acids, I made a video going into great detail about them so check that out below:

The second type of food I like are dry powdered plankton. There are several different types on the market and I take the three or four I have on hand at any given time, mix them all up and when it is feeding time, make a cloudy solution with them to broadcast feed over the Goniopora colonies.

The best technique I have found is to completely turn off the pumps so that nothing blows away in the current and then spray a cloud of food over each colony with a turkey baster. The particles should be fine enough that the fish won�t come and harass the coral, but even if they do, you can apply another dusting after a few minutes. After about 15-20 min I then start the pumps back up. Some hobbyists leave the pumps off for longer than that, so you may want to experiment a little bit to see what works best in your tank.

Although coral nutrition is important, there is such a thing as too much of a good thing. If you are going to experiment with broadcast feeding or target feeding, start slowly with it and don�t expect explosive changes overnight. Having some phosphate and nitrate in the water is beneficial but overfeeding can cause these parameters to rise to dangerous levels that can be hard to remedy.

Name: Goniopora sp.Temperature: 24-26C Flow: low-mid PAR: 75-150Water parameters: Nitrate 5-20 mg/l, Phosphate 0,05-0,15 mg/l Feeding: They are adept feeders that can grab and consume a wide variety of foods ranging from coral-formulated sinking pellets to frozen food such as brine shrimp, mysis, and krill. Care level: Moderade Location Part of the reason for the recent success is sourcing the coral. There are around 20 different species of Goniopora and some are more hardy than others. We have had the best success with Goniopora that originated in Australia. They tend to have better coloration and smaller polyps than the ones I�ve seen come from other geographies like Indonesia. Lighting Goniopora are a photosynthetic coral so they derive some of their nutritional requirements from light. This is done through a symbiotic relationship with dinoflagellates called zooxanthellae that live in the flesh of the coral. The dinoflagellates are actually the photosynthetic organism and the Goniopora colony derives nutrients off of the byproducts of the dinoflagellates� photosynthetic process. Zooxanthellae is usually brown in color and the coral tightly regulates the population living in its flesh. Too little light will cause the coral to turn brown in color. As it seeks more nutrition, the coral allows more zooxanthellae to build up in its flesh. Usually a coral will prefer a specific range of lighting intensity but that is less of the case with Goniopora. Goniopora can thrive in a wide range of lighting. We have kept Goniopora in different lighting intensities here at Wild Corals_ranging from very dimly lit 50 PAR tanks all the way to bright aquariums receiving over 200 PAR. I would recommend placing them under moderate lighting intensities, between 75-125 PAR. Goniopora are consistent in their appearance under different lighting. That is to say that a red colored Goniopora won�t suddenly turn green when moved to another aquarium with slightly different lights above it. Sounds strange, but there are plenty of corals out there that can shift their color palate like that. Having said that, the type of lighting system chosen will have a dramatic effect on how they are displayed. There are some incredibly fluorescent varieties of Goniopora that glow like safety cones under the right blend of actinic lights which would not be apparent at all under daylight lighting. Water Flow One of my favorite things about Goniopora is how the tentacles sway in the current. It is one of the most dramatic and aesthetically pleasing large polyp stony corals as far as motion is concerned. It�s movement is almost hypnotic and is one of the things that makes Goniopora such a great focal point in the aquarium. One mistake I think some reef keepers make is providing them too much flow. If you have a powerhead blowing right at Goniopora from short range, it may kill off some of the tissue at that point of contact and cause a chain reaction to the rest of the colony. Goniopora appreciate low to medium flow, but preferably with some randomness to it. That way you will get that gentle waving motion which helps keep the coral clean and brings food past the colony. If you see the tentacles violently thrashing about, that is probably too much flow and it would benefit from being relocated to a more calm section of the tank. Feeding Perhaps the biggest difference between the time when aquarists struggled keeping Goniopora to now is the change in mentality regarding coral feeding. For decades the majority of hobbyists believed that feeding was not necessary. Fast forward to today and well€ the majority probably still don�t But_at least now there are more resources available demonstrating the positive benefits of feeding as well as a variety of coral foods in both powder and liquid form on the market. I am absolutely convinced that Goniopora have to be fed and fed a lot. I�ve kept a lot of different types of Goniopora and just a personal anecdote, the times I�ve struggled with them had to do with neglect and lack of feeding. When I diligently provided them with a high quality food source, they almost always thrived. What to feed Goniopora is a good question. Goniopora do not put on dramatic feeding displays like some large polyp stony corals. In fact, they seem to shy away from contact rather than aggressively trying to capture food. They have this Ðpogo hopperÓ motion to their polyps when food is introduced. Some believe that the coral takes in a lot of their nutrients through their skin more so than consuming it with their mouth, so even if you don�t see it actively feeding trust that something positive is still happening. There are two types of food that I like to provide Goniopora. The first is liquid amino acids. In short, they are simple organic compounds that play a major role in building proteins as well as other biological functions at the cellular level. Corals regularly take in available amino acids from the water column so it is easy to provide them with adequate quantities by broadcast feeding an amino acid solution. If you want to know more about amino acids, I made a video going into great detail about them so check that out below: The second type of food I like are dry powdered plankton. There are several different types on the market and I take the three or four I have on hand at any given time, mix them all up and when it is feeding time, make a cloudy solution with them to broadcast feed over the Goniopora colonies. The best technique I have found is to completely turn off the pumps so that nothing blows away in the current and then spray a cloud of food over each colony with a turkey baster. The particles should be fine enough that the fish won�t come and harass the coral, but even if they do, you can apply another dusting after a few minutes. After about 15-20 min I then start the pumps back up. Some hobbyists leave the pumps off for longer than that, so you may want to experiment a little bit to see what works best in your tank. Although coral nutrition is important, there is such a thing as too much of a good thing. If you are going to experiment with broadcast feeding or target feeding, start slowly with it and don�t expect explosive changes overnight. Having some phosphate and nitrate in the water is beneficial but overfeeding can cause these parameters to rise to dangerous levels that can be hard to remedy.

€29,00

SKU: EG210

Euphyllia like Hammer corals are found all over the tropical waters of the Pacific. In particular, they are regularly harvested from the islands of the Indopacific including Fiji, Tonga, Solomon Islands, and the Great Barrier Reef.

Torch corals are LPS meaning as stony corals, they require consistent levels of calcium, alkalinity, and to a lesser degree magnesium in order to grow their calcium carbonate skeleton. The amount of supplementation needed to maintain calcium, alkalinity, and magnesium depends a lot on the size and growth rate of the stony corals in your tank.

Torch corals are LPS meaning as stony corals, they require consistent levels of calcium, alkalinity, and to a lesser degree magnesium in order to grow their calcium carbonate skeleton. The amount of supplementation needed to maintain calcium, alkalinity, and magnesium depends a lot on the size and growth rate of the stony corals in your tank. Agonizing over these levels might be mental overkill for this coral, but it is good to periodically test just to make sure everything is in the ballpark of natural sea water levels. A couple parameters worth paying closer attention to is nitrate and phosphate. LPS corals are sensitive to declining water quality and elevated levels of nitrate and phosphate are an indicator of declining water quality. Low nitrate levels around 5-10ppm are actually welcome for large polyp stony corals, but around 30-40ppm of nitrate you might start running into some issues such as tissue recession. In extreme cases, you might see a torch coral go through full-fledged polyp bailout which we will cover in a little bit.

Corals developed all kinds of adaptations to gain a competitive advantage in the battle for real estate on the reef. In our home aquariums we have to be conscious of these in order to create the best environment for them long term. Euphyllia are one of the corals that extends long sweeper tentacles. Sweeper tentacles are often used as a means of defence against other encroaching coral colonies. Their white tips contain a concentration of nematocysts that can damage more delicate tank mates. Most of the time, this is not a major problem but to be safe, we recommend placing it in a location far from other corals initially. Like most coral, Euphyllia rely to a large extent on the products of their zooxanthellae, however, in our experience, they also benefit from direct feeding. Hammers, torches, and frogspawn do not seem to aggressively feed like other LPS, so finding the right food can be a challenge.

Name: Euphyllia Glabrescens Temperature: 24-26C Flow: low-mid PAR: 50-150 Water parameters: Nitrate 5-20 mg/l, Phosphate 0,05-0,15 mg/l Feeding: No feeding required, but may be fed plankton (e.g. Goldpods) if desired Care level: Easy/Moderated Location Euphyllia like Hammer corals are found all over the tropical waters of the Pacific. In particular, they are regularly harvested from the islands of the Indopacific including Fiji, Tonga, Solomon Islands, and the Great Barrier Reef. Lighting Torch corals are LPS meaning as stony corals, they require consistent levels of calcium, alkalinity, and to a lesser degree magnesium in order to grow their calcium carbonate skeleton. The amount of supplementation needed to maintain calcium, alkalinity, and magnesium depends a lot on the size and growth rate of the stony corals in your tank. Water Flow Moderate to strong water movement is recommended. One of the main draws to this type of LPS coral is how it sways in the current. Water flow is both healthy for the Hammer and is pleasing aesthetically. Water Chemistry Torch corals are LPS meaning as stony corals, they require consistent levels of calcium, alkalinity, and to a lesser degree magnesium in order to grow their calcium carbonate skeleton. The amount of supplementation needed to maintain calcium, alkalinity, and magnesium depends a lot on the size and growth rate of the stony corals in your tank. Agonizing over these levels might be mental overkill for this coral, but it is good to periodically test just to make sure everything is in the ballpark of natural sea water levels. A couple parameters worth paying closer attention to is nitrate and phosphate. LPS corals are sensitive to declining water quality and elevated levels of nitrate and phosphate are an indicator of declining water quality. Low nitrate levels around 5-10ppm are actually welcome for large polyp stony corals, but around 30-40ppm of nitrate you might start running into some issues such as tissue recession. In extreme cases, you might see a torch coral go through full-fledged polyp bailout which we will cover in a little bit. Coral Aggression Corals developed all kinds of adaptations to gain a competitive advantage in the battle for real estate on the reef. In our home aquariums we have to be conscious of these in order to create the best environment for them long term. Euphyllia are one of the corals that extends long sweeper tentacles. Sweeper tentacles are often used as a means of defence against other encroaching coral colonies. Their white tips contain a concentration of nematocysts that can damage more delicate tank mates. Most of the time, this is not a major problem but to be safe, we recommend placing it in a location far from other corals initially. Like most coral, Euphyllia rely to a large extent on the products of their zooxanthellae, however, in our experience, they also benefit from direct feeding. Hammers, torches, and frogspawn do not seem to aggressively feed like other LPS, so finding the right food can be a challenge.

€299,00€249,00

SKU:

Acanthophyllia are a large polyp stony coral often referred to as a donut or meat coral. They are similar in appearance to Scolymia/Homophyllia or Cynarina in that they are a single polyp, round in shape, and often times come in some dazzling colors and patterns.

Seven years ago, I did a video on this coral and the title was something like ÒAcanthophyllia are an underrated LPS.Ó These days that could not be further from the truth. Nowadays, Acanthophyllia are highly desired among collectors of large polyp stony corals and I would go as far as to say that they are the absolute pinnacle for those looking for that signature show piece.

The obvious downside to that level of demand is the price point for these guys. They are some of the most expensive corals in the industry.

Luckily despite the prices, Acanthophyllia tend to be one of the more hardy corals out there. There are some corals that are notoriously sensitive and it is always a scare to drop serious money into a coral that is known to be challenging. Acanthophyllia are the opposite end of the spectrum. They can be housed in a wide range of tank conditions and can handle a modest degree of neglect. You really canÕt say that about a high end Acropora for example.

The only thing I would mention about its hardiness is when it comes to shipping this coral. Shipping is always a stressful event for any coral but it can be particularly damaging for Acanthophyllia. Under all that flesh is one of the spikiest skeletons IÕve seen on any coral. This is troublesome for two reasons, the first is it can poke through shipping bags thus causing leaks and if you are shipping in cold weather, the leaking water can deactivate the heating packs in the box. Big yikes. So when it comes to packing these guys we donÕt skimp on the bags. I know IÕve used up to four giant 3-mil bags to send them out.

The second problem with their spiky skeleton is that they can damage their skin during transit. Evan assuming they donÕt punch through the bag as they roll around, the spikes skeleton does poke through their skin. Like I said though, it is a good thing this coral is pretty tough because it does not take long for the coral to settle into an established reef aquarium and heal over that damage.

Acanthophyllia are found throughout Indonesia and Australia. The specimens from Australia are predominantly that greenish blue mint-chocolate chip appearance. The specimens from Indonesia are mostly red and blue, but there are rare color variants that are all the colors of the rainbow. Those are the most desirable.

Depending on the colors high end collectors are willing to pay well into the four figures, and occasionally I see a truly stunning piece that I can imagine someone spending a fortune on. Part of the reason for their scarcity is their availability in some countries. Right around the time of the Indonesian export ban in 2018, there were changes in what corals could be sent where and from what I understand Acanthophyllia was one of the most restricted corals once things opened back up.

Here in the US they are still being brought in, but the prices are much higher than before. As for the future of the imports and exports for this coral, that remains unclear.

The other aspect affecting its price is the fact that there are no good aquacultured sources for Acanthophyllia. They cannot be cut and sexual reproduction hasnÕt been accomplished on a commercial scale. Hopefully that changes in the future! That would be game changing, but we are talking about a monumental challenge given the difficulty associated with sexual reproduction on the commercial scale and the incredible slow growth of this coral.

ThatÕs a little bit of background on Acanthophyllia. LetÕs now talk about their care requirements starting with lighting and placement.

We primarily keep Acanthophyllia in low to medium light intensity here at Tidal Gardens which is around 50 to 100 PAR. We have kept them in higher lighting but they did not appear to appreciate it and were always at risk of bleaching out. If you have a colony of Acanthophyllia and want to experiment with higher light, remember that it can be a risk, so be prepared to move it into a shadier region of the tank at the first signs of trouble.

As for placement, almost every tank I see these corals in keeps them at the bottom of the tank regardless of whether it has a substrate or bare bottom. They settle in nicely down there are when they are happy will extend nicely and take on that ChiliÕs lava cake appearance. I suppose there isnÕt a good reason that they couldnÕt be put up on a rock scape, but it is much less common. Perhaps the thinking is that higher up on the rock scape would expose the coral to more light and more flow which might not be the best combination for this coral.

One other thing about placement to consider is to consider how much it will spread out once it settles into your reef tank. Acanthophyllia do not grow fast AT ALL, but they can swell many times larger than their skeleton so you want to avoid a situation where this coral reaches out and covers its neighbors.

LetÕs move on to water flow. We touched on it briefly in regards to placement, but I would prioritize finding an ideal location with regard to flow more so than lighting. Being such a fleshy coral you donÕt want to give it too much flow to the point that the skeleton starts to poke through the flesh. It can absolutely happen if the Acanthophyllia is getting hit continuously by a strong laminar flow.

As a general recommendation, I would keep an Acanthophyllia in a low to medium flow area and preferably one with variable flow patterns so one side of the coral doesnÕt get hit constantly. Normally I would be concerned about a coral placed on the bottom collecting detritus, but that is more of an issue with small polyp stony corals or large polyp stony corals that grow into a bowl-like shape. Acanthophyllia donÕt have any difficulty shrugging off detritus that settles on them so they can be kept in lower flow than most without issue.

The lower flow also makes it much easier to feed.

If you enjoy spot feeding your corals, you are in for a treat. Acanthophyllia exhibit one of the most dramatic feeding displays when it opens up. They practically turn themselves inside out to completely transform into a giant seafood receptacle.

They can be fed a variety of foods, so I wouldnÕt overthink it too much when selecting something to give them. LPS pellets or full sized krill would work fine. WeÕve even fed them larger items like silversides in the past.

What is kind of strange is how Acanthophyllia reacts to different food. One behavior IÕve seen is that it reacts the most enthusiastically to really small planktonic foods especially frozen rotifers. The colony opens way up but it is hard to tell if it is actually eating anything. I have a feeling that they are taking it in through their mucus coat it is just that their tentacles are not engaged in prey capture during that time.

Once it is fed larger chunkier food though it actively takes them in.

Another thing you can do in terms of feeding that isn't completely necessary, but will help keep your corals on the healthier side, is to feed them amino acids as well

Amino Acids are simple organic compounds that play a major role in building proteins as well as other biological functions at the cellular level. There are a little over 20 different types of amino acids. Most of them can be synthesized by the organism but some cannot be and must be taken in by feeding. Those amino acids are termed essential amino acids and they vary from species to species. Corals regularly take in available amino acids from the water column so it is easy to provide them with adequate quantities by broadcast feeding an amino acid solution. They are available from any number of commercially available reef supplement manufacturers. This may be the easiest way to feed your corals because as long as amino acids are bioavailable in the water column, the corals will soak them up.

Ê

Name: Acanthophyllia Temperature: 24-26C Flow: low-mid PAR: 50-150 Water parameters: Nitrate 5-20 mg/l, Phosphate 0,05-0,15 mg/l Feeding: Feeding is desired. Care level: Easy/Moderated Acanthophyllia are a large polyp stony coral often referred to as a donut or meat coral. They are similar in appearance to Scolymia/Homophyllia or Cynarina in that they are a single polyp, round in shape, and often times come in some dazzling colors and patterns. Seven years ago, I did a video on this coral and the title was something like ÒAcanthophyllia are an underrated LPS.Ó These days that could not be further from the truth. Nowadays, Acanthophyllia are highly desired among collectors of large polyp stony corals and I would go as far as to say that they are the absolute pinnacle for those looking for that signature show piece. The obvious downside to that level of demand is the price point for these guys. They are some of the most expensive corals in the industry. Luckily despite the prices, Acanthophyllia tend to be one of the more hardy corals out there. There are some corals that are notoriously sensitive and it is always a scare to drop serious money into a coral that is known to be challenging. Acanthophyllia are the opposite end of the spectrum. They can be housed in a wide range of tank conditions and can handle a modest degree of neglect. You really canÕt say that about a high end Acropora for example. The only thing I would mention about its hardiness is when it comes to shipping this coral. Shipping is always a stressful event for any coral but it can be particularly damaging for Acanthophyllia. Under all that flesh is one of the spikiest skeletons IÕve seen on any coral. This is troublesome for two reasons, the first is it can poke through shipping bags thus causing leaks and if you are shipping in cold weather, the leaking water can deactivate the heating packs in the box. Big yikes. So when it comes to packing these guys we donÕt skimp on the bags. I know IÕve used up to four giant 3-mil bags to send them out. The second problem with their spiky skeleton is that they can damage their skin during transit. Evan assuming they donÕt punch through the bag as they roll around, the spikes skeleton does poke through their skin. Like I said though, it is a good thing this coral is pretty tough because it does not take long for the coral to settle into an established reef aquarium and heal over that damage. Location Acanthophyllia are found throughout Indonesia and Australia. The specimens from Australia are predominantly that greenish blue mint-chocolate chip appearance. The specimens from Indonesia are mostly red and blue, but there are rare color variants that are all the colors of the rainbow. Those are the most desirable. Depending on the colors high end collectors are willing to pay well into the four figures, and occasionally I see a truly stunning piece that I can imagine someone spending a fortune on. Part of the reason for their scarcity is their availability in some countries. Right around the time of the Indonesian export ban in 2018, there were changes in what corals could be sent where and from what I understand Acanthophyllia was one of the most restricted corals once things opened back up. Here in the US they are still being brought in, but the prices are much higher than before. As for the future of the imports and exports for this coral, that remains unclear. The other aspect affecting its price is the fact that there are no good aquacultured sources for Acanthophyllia. They cannot be cut and sexual reproduction hasnÕt been accomplished on a commercial scale. Hopefully that changes in the future! That would be game changing, but we are talking about a monumental challenge given the difficulty associated with sexual reproduction on the commercial scale and the incredible slow growth of this coral. ThatÕs a little bit of background on Acanthophyllia. LetÕs now talk about their care requirements starting with lighting and placement. Lighting We primarily keep Acanthophyllia in low to medium light intensity here at Tidal Gardens which is around 50 to 100 PAR. We have kept them in higher lighting but they did not appear to appreciate it and were always at risk of bleaching out. If you have a colony of Acanthophyllia and want to experiment with higher light, remember that it can be a risk, so be prepared to move it into a shadier region of the tank at the first signs of trouble. As for placement, almost every tank I see these corals in keeps them at the bottom of the tank regardless of whether it has a substrate or bare bottom. They settle in nicely down there are when they are happy will extend nicely and take on that ChiliÕs lava cake appearance. I suppose there isnÕt a good reason that they couldnÕt be put up on a rock scape, but it is much less common. Perhaps the thinking is that higher up on the rock scape would expose the coral to more light and more flow which might not be the best combination for this coral. One other thing about placement to consider is to consider how much it will spread out once it settles into your reef tank. Acanthophyllia do not grow fast AT ALL, but they can swell many times larger than their skeleton so you want to avoid a situation where this coral reaches out and covers its neighbors. Water Flow LetÕs move on to water flow. We touched on it briefly in regards to placement, but I would prioritize finding an ideal location with regard to flow more so than lighting. Being such a fleshy coral you donÕt want to give it too much flow to the point that the skeleton starts to poke through the flesh. It can absolutely happen if the Acanthophyllia is getting hit continuously by a strong laminar flow. As a general recommendation, I would keep an Acanthophyllia in a low to medium flow area and preferably one with variable flow patterns so one side of the coral doesnÕt get hit constantly. Normally I would be concerned about a coral placed on the bottom collecting detritus, but that is more of an issue with small polyp stony corals or large polyp stony corals that grow into a bowl-like shape. Acanthophyllia donÕt have any difficulty shrugging off detritus that settles on them so they can be kept in lower flow than most without issue. The lower flow also makes it much easier to feed. Feeding If you enjoy spot feeding your corals, you are in for a treat. Acanthophyllia exhibit one of the most dramatic feeding displays when it opens up. They practically turn themselves inside out to completely transform into a giant seafood receptacle. They can be fed a variety of foods, so I wouldnÕt overthink it too much when selecting something to give them. LPS pellets or full sized krill would work fine. WeÕve even fed them larger items like silversides in the past. What is kind of strange is how Acanthophyllia reacts to different food. One behavior IÕve seen is that it reacts the most enthusiastically to really small planktonic foods especially frozen rotifers. The colony opens way up but it is hard to tell if it is actually eating anything. I have a feeling that they are taking it in through their mucus coat it is just that their tentacles are not engaged in prey capture during that time. Once it is fed larger chunkier food though it actively takes them in. Another thing you can do in terms of feeding that isn't completely necessary, but will help keep your corals on the healthier side, is to feed them amino acids as well Amino Acids are simple organic compounds that play a major role in building proteins as well as other biological functions at the cellular level. There are a little over 20 different types of amino acids. Most of them can be synthesized by the organism but some cannot be and must be taken in by feeding. Those amino acids are termed essential amino acids and they vary from species to species. Corals regularly take in available amino acids from the water column so it is easy to provide them with adequate quantities by broadcast feeding an amino acid solution. They are available from any number of commercially available reef supplement manufacturers. This may be the easiest way to feed your corals because as long as amino acids are bioavailable in the water column, the corals will soak them up. Ê

€799,00€499,00

SKU:

Acanthophyllia are a large polyp stony coral often referred to as a donut or meat coral. They are similar in appearance to Scolymia/Homophyllia or Cynarina in that they are a single polyp, round in shape, and often times come in some dazzling colors and patterns.

Seven years ago, I did a video on this coral and the title was something like ÒAcanthophyllia are an underrated LPS.Ó These days that could not be further from the truth. Nowadays, Acanthophyllia are highly desired among collectors of large polyp stony corals and I would go as far as to say that they are the absolute pinnacle for those looking for that signature show piece.

The obvious downside to that level of demand is the price point for these guys. They are some of the most expensive corals in the industry.

Luckily despite the prices, Acanthophyllia tend to be one of the more hardy corals out there. There are some corals that are notoriously sensitive and it is always a scare to drop serious money into a coral that is known to be challenging. Acanthophyllia are the opposite end of the spectrum. They can be housed in a wide range of tank conditions and can handle a modest degree of neglect. You really canÕt say that about a high end Acropora for example.

The only thing I would mention about its hardiness is when it comes to shipping this coral. Shipping is always a stressful event for any coral but it can be particularly damaging for Acanthophyllia. Under all that flesh is one of the spikiest skeletons IÕve seen on any coral. This is troublesome for two reasons, the first is it can poke through shipping bags thus causing leaks and if you are shipping in cold weather, the leaking water can deactivate the heating packs in the box. Big yikes. So when it comes to packing these guys we donÕt skimp on the bags. I know IÕve used up to four giant 3-mil bags to send them out.

The second problem with their spiky skeleton is that they can damage their skin during transit. Evan assuming they donÕt punch through the bag as they roll around, the spikes skeleton does poke through their skin. Like I said though, it is a good thing this coral is pretty tough because it does not take long for the coral to settle into an established reef aquarium and heal over that damage.

Acanthophyllia are found throughout Indonesia and Australia. The specimens from Australia are predominantly that greenish blue mint-chocolate chip appearance. The specimens from Indonesia are mostly red and blue, but there are rare color variants that are all the colors of the rainbow. Those are the most desirable.

Depending on the colors high end collectors are willing to pay well into the four figures, and occasionally I see a truly stunning piece that I can imagine someone spending a fortune on. Part of the reason for their scarcity is their availability in some countries. Right around the time of the Indonesian export ban in 2018, there were changes in what corals could be sent where and from what I understand Acanthophyllia was one of the most restricted corals once things opened back up.

Here in the US they are still being brought in, but the prices are much higher than before. As for the future of the imports and exports for this coral, that remains unclear.

The other aspect affecting its price is the fact that there are no good aquacultured sources for Acanthophyllia. They cannot be cut and sexual reproduction hasnÕt been accomplished on a commercial scale. Hopefully that changes in the future! That would be game changing, but we are talking about a monumental challenge given the difficulty associated with sexual reproduction on the commercial scale and the incredible slow growth of this coral.

ThatÕs a little bit of background on Acanthophyllia. LetÕs now talk about their care requirements starting with lighting and placement.

We primarily keep Acanthophyllia in low to medium light intensity here at Tidal Gardens which is around 50 to 100 PAR. We have kept them in higher lighting but they did not appear to appreciate it and were always at risk of bleaching out. If you have a colony of Acanthophyllia and want to experiment with higher light, remember that it can be a risk, so be prepared to move it into a shadier region of the tank at the first signs of trouble.

As for placement, almost every tank I see these corals in keeps them at the bottom of the tank regardless of whether it has a substrate or bare bottom. They settle in nicely down there are when they are happy will extend nicely and take on that ChiliÕs lava cake appearance. I suppose there isnÕt a good reason that they couldnÕt be put up on a rock scape, but it is much less common. Perhaps the thinking is that higher up on the rock scape would expose the coral to more light and more flow which might not be the best combination for this coral.

One other thing about placement to consider is to consider how much it will spread out once it settles into your reef tank. Acanthophyllia do not grow fast AT ALL, but they can swell many times larger than their skeleton so you want to avoid a situation where this coral reaches out and covers its neighbors.

LetÕs move on to water flow. We touched on it briefly in regards to placement, but I would prioritize finding an ideal location with regard to flow more so than lighting. Being such a fleshy coral you donÕt want to give it too much flow to the point that the skeleton starts to poke through the flesh. It can absolutely happen if the Acanthophyllia is getting hit continuously by a strong laminar flow.

As a general recommendation, I would keep an Acanthophyllia in a low to medium flow area and preferably one with variable flow patterns so one side of the coral doesnÕt get hit constantly. Normally I would be concerned about a coral placed on the bottom collecting detritus, but that is more of an issue with small polyp stony corals or large polyp stony corals that grow into a bowl-like shape. Acanthophyllia donÕt have any difficulty shrugging off detritus that settles on them so they can be kept in lower flow than most without issue.

The lower flow also makes it much easier to feed.

If you enjoy spot feeding your corals, you are in for a treat. Acanthophyllia exhibit one of the most dramatic feeding displays when it opens up. They practically turn themselves inside out to completely transform into a giant seafood receptacle.

They can be fed a variety of foods, so I wouldnÕt overthink it too much when selecting something to give them. LPS pellets or full sized krill would work fine. WeÕve even fed them larger items like silversides in the past.

What is kind of strange is how Acanthophyllia reacts to different food. One behavior IÕve seen is that it reacts the most enthusiastically to really small planktonic foods especially frozen rotifers. The colony opens way up but it is hard to tell if it is actually eating anything. I have a feeling that they are taking it in through their mucus coat it is just that their tentacles are not engaged in prey capture during that time.

Once it is fed larger chunkier food though it actively takes them in.

Another thing you can do in terms of feeding that isn't completely necessary, but will help keep your corals on the healthier side, is to feed them amino acids as well

Amino Acids are simple organic compounds that play a major role in building proteins as well as other biological functions at the cellular level. There are a little over 20 different types of amino acids. Most of them can be synthesized by the organism but some cannot be and must be taken in by feeding. Those amino acids are termed essential amino acids and they vary from species to species. Corals regularly take in available amino acids from the water column so it is easy to provide them with adequate quantities by broadcast feeding an amino acid solution. They are available from any number of commercially available reef supplement manufacturers. This may be the easiest way to feed your corals because as long as amino acids are bioavailable in the water column, the corals will soak them up.

Ê

Name: Acanthophyllia Temperature: 24-26C Flow: low-mid PAR: 50-150 Water parameters: Nitrate 5-20 mg/l, Phosphate 0,05-0,15 mg/l Feeding: Feeding is desired. Care level: Easy/Moderated Acanthophyllia are a large polyp stony coral often referred to as a donut or meat coral. They are similar in appearance to Scolymia/Homophyllia or Cynarina in that they are a single polyp, round in shape, and often times come in some dazzling colors and patterns. Seven years ago, I did a video on this coral and the title was something like ÒAcanthophyllia are an underrated LPS.Ó These days that could not be further from the truth. Nowadays, Acanthophyllia are highly desired among collectors of large polyp stony corals and I would go as far as to say that they are the absolute pinnacle for those looking for that signature show piece. The obvious downside to that level of demand is the price point for these guys. They are some of the most expensive corals in the industry. Luckily despite the prices, Acanthophyllia tend to be one of the more hardy corals out there. There are some corals that are notoriously sensitive and it is always a scare to drop serious money into a coral that is known to be challenging. Acanthophyllia are the opposite end of the spectrum. They can be housed in a wide range of tank conditions and can handle a modest degree of neglect. You really canÕt say that about a high end Acropora for example. The only thing I would mention about its hardiness is when it comes to shipping this coral. Shipping is always a stressful event for any coral but it can be particularly damaging for Acanthophyllia. Under all that flesh is one of the spikiest skeletons IÕve seen on any coral. This is troublesome for two reasons, the first is it can poke through shipping bags thus causing leaks and if you are shipping in cold weather, the leaking water can deactivate the heating packs in the box. Big yikes. So when it comes to packing these guys we donÕt skimp on the bags. I know IÕve used up to four giant 3-mil bags to send them out. The second problem with their spiky skeleton is that they can damage their skin during transit. Evan assuming they donÕt punch through the bag as they roll around, the spikes skeleton does poke through their skin. Like I said though, it is a good thing this coral is pretty tough because it does not take long for the coral to settle into an established reef aquarium and heal over that damage. Location Acanthophyllia are found throughout Indonesia and Australia. The specimens from Australia are predominantly that greenish blue mint-chocolate chip appearance. The specimens from Indonesia are mostly red and blue, but there are rare color variants that are all the colors of the rainbow. Those are the most desirable. Depending on the colors high end collectors are willing to pay well into the four figures, and occasionally I see a truly stunning piece that I can imagine someone spending a fortune on. Part of the reason for their scarcity is their availability in some countries. Right around the time of the Indonesian export ban in 2018, there were changes in what corals could be sent where and from what I understand Acanthophyllia was one of the most restricted corals once things opened back up. Here in the US they are still being brought in, but the prices are much higher than before. As for the future of the imports and exports for this coral, that remains unclear. The other aspect affecting its price is the fact that there are no good aquacultured sources for Acanthophyllia. They cannot be cut and sexual reproduction hasnÕt been accomplished on a commercial scale. Hopefully that changes in the future! That would be game changing, but we are talking about a monumental challenge given the difficulty associated with sexual reproduction on the commercial scale and the incredible slow growth of this coral. ThatÕs a little bit of background on Acanthophyllia. LetÕs now talk about their care requirements starting with lighting and placement. Lighting We primarily keep Acanthophyllia in low to medium light intensity here at Tidal Gardens which is around 50 to 100 PAR. We have kept them in higher lighting but they did not appear to appreciate it and were always at risk of bleaching out. If you have a colony of Acanthophyllia and want to experiment with higher light, remember that it can be a risk, so be prepared to move it into a shadier region of the tank at the first signs of trouble. As for placement, almost every tank I see these corals in keeps them at the bottom of the tank regardless of whether it has a substrate or bare bottom. They settle in nicely down there are when they are happy will extend nicely and take on that ChiliÕs lava cake appearance. I suppose there isnÕt a good reason that they couldnÕt be put up on a rock scape, but it is much less common. Perhaps the thinking is that higher up on the rock scape would expose the coral to more light and more flow which might not be the best combination for this coral. One other thing about placement to consider is to consider how much it will spread out once it settles into your reef tank. Acanthophyllia do not grow fast AT ALL, but they can swell many times larger than their skeleton so you want to avoid a situation where this coral reaches out and covers its neighbors. Water Flow LetÕs move on to water flow. We touched on it briefly in regards to placement, but I would prioritize finding an ideal location with regard to flow more so than lighting. Being such a fleshy coral you donÕt want to give it too much flow to the point that the skeleton starts to poke through the flesh. It can absolutely happen if the Acanthophyllia is getting hit continuously by a strong laminar flow. As a general recommendation, I would keep an Acanthophyllia in a low to medium flow area and preferably one with variable flow patterns so one side of the coral doesnÕt get hit constantly. Normally I would be concerned about a coral placed on the bottom collecting detritus, but that is more of an issue with small polyp stony corals or large polyp stony corals that grow into a bowl-like shape. Acanthophyllia donÕt have any difficulty shrugging off detritus that settles on them so they can be kept in lower flow than most without issue. The lower flow also makes it much easier to feed. Feeding If you enjoy spot feeding your corals, you are in for a treat. Acanthophyllia exhibit one of the most dramatic feeding displays when it opens up. They practically turn themselves inside out to completely transform into a giant seafood receptacle. They can be fed a variety of foods, so I wouldnÕt overthink it too much when selecting something to give them. LPS pellets or full sized krill would work fine. WeÕve even fed them larger items like silversides in the past. What is kind of strange is how Acanthophyllia reacts to different food. One behavior IÕve seen is that it reacts the most enthusiastically to really small planktonic foods especially frozen rotifers. The colony opens way up but it is hard to tell if it is actually eating anything. I have a feeling that they are taking it in through their mucus coat it is just that their tentacles are not engaged in prey capture during that time. Once it is fed larger chunkier food though it actively takes them in. Another thing you can do in terms of feeding that isn't completely necessary, but will help keep your corals on the healthier side, is to feed them amino acids as well Amino Acids are simple organic compounds that play a major role in building proteins as well as other biological functions at the cellular level. There are a little over 20 different types of amino acids. Most of them can be synthesized by the organism but some cannot be and must be taken in by feeding. Those amino acids are termed essential amino acids and they vary from species to species. Corals regularly take in available amino acids from the water column so it is easy to provide them with adequate quantities by broadcast feeding an amino acid solution. They are available from any number of commercially available reef supplement manufacturers. This may be the easiest way to feed your corals because as long as amino acids are bioavailable in the water column, the corals will soak them up. Ê

€1.299,00€999,00

SKU:

Acanthophyllia are a large polyp stony coral often referred to as a donut or meat coral. They are similar in appearance to Scolymia/Homophyllia or Cynarina in that they are a single polyp, round in shape, and often times come in some dazzling colors and patterns.

Seven years ago, I did a video on this coral and the title was something like ÒAcanthophyllia are an underrated LPS.Ó These days that could not be further from the truth. Nowadays, Acanthophyllia are highly desired among collectors of large polyp stony corals and I would go as far as to say that they are the absolute pinnacle for those looking for that signature show piece.

The obvious downside to that level of demand is the price point for these guys. They are some of the most expensive corals in the industry.

Luckily despite the prices, Acanthophyllia tend to be one of the more hardy corals out there. There are some corals that are notoriously sensitive and it is always a scare to drop serious money into a coral that is known to be challenging. Acanthophyllia are the opposite end of the spectrum. They can be housed in a wide range of tank conditions and can handle a modest degree of neglect. You really canÕt say that about a high end Acropora for example.

The only thing I would mention about its hardiness is when it comes to shipping this coral. Shipping is always a stressful event for any coral but it can be particularly damaging for Acanthophyllia. Under all that flesh is one of the spikiest skeletons IÕve seen on any coral. This is troublesome for two reasons, the first is it can poke through shipping bags thus causing leaks and if you are shipping in cold weather, the leaking water can deactivate the heating packs in the box. Big yikes. So when it comes to packing these guys we donÕt skimp on the bags. I know IÕve used up to four giant 3-mil bags to send them out.

The second problem with their spiky skeleton is that they can damage their skin during transit. Evan assuming they donÕt punch through the bag as they roll around, the spikes skeleton does poke through their skin. Like I said though, it is a good thing this coral is pretty tough because it does not take long for the coral to settle into an established reef aquarium and heal over that damage.

Acanthophyllia are found throughout Indonesia and Australia. The specimens from Australia are predominantly that greenish blue mint-chocolate chip appearance. The specimens from Indonesia are mostly red and blue, but there are rare color variants that are all the colors of the rainbow. Those are the most desirable.

Depending on the colors high end collectors are willing to pay well into the four figures, and occasionally I see a truly stunning piece that I can imagine someone spending a fortune on. Part of the reason for their scarcity is their availability in some countries. Right around the time of the Indonesian export ban in 2018, there were changes in what corals could be sent where and from what I understand Acanthophyllia was one of the most restricted corals once things opened back up.

Here in the US they are still being brought in, but the prices are much higher than before. As for the future of the imports and exports for this coral, that remains unclear.

The other aspect affecting its price is the fact that there are no good aquacultured sources for Acanthophyllia. They cannot be cut and sexual reproduction hasnÕt been accomplished on a commercial scale. Hopefully that changes in the future! That would be game changing, but we are talking about a monumental challenge given the difficulty associated with sexual reproduction on the commercial scale and the incredible slow growth of this coral.

ThatÕs a little bit of background on Acanthophyllia. LetÕs now talk about their care requirements starting with lighting and placement.

We primarily keep Acanthophyllia in low to medium light intensity here at Tidal Gardens which is around 50 to 100 PAR. We have kept them in higher lighting but they did not appear to appreciate it and were always at risk of bleaching out. If you have a colony of Acanthophyllia and want to experiment with higher light, remember that it can be a risk, so be prepared to move it into a shadier region of the tank at the first signs of trouble.

As for placement, almost every tank I see these corals in keeps them at the bottom of the tank regardless of whether it has a substrate or bare bottom. They settle in nicely down there are when they are happy will extend nicely and take on that ChiliÕs lava cake appearance. I suppose there isnÕt a good reason that they couldnÕt be put up on a rock scape, but it is much less common. Perhaps the thinking is that higher up on the rock scape would expose the coral to more light and more flow which might not be the best combination for this coral.

One other thing about placement to consider is to consider how much it will spread out once it settles into your reef tank. Acanthophyllia do not grow fast AT ALL, but they can swell many times larger than their skeleton so you want to avoid a situation where this coral reaches out and covers its neighbors.

LetÕs move on to water flow. We touched on it briefly in regards to placement, but I would prioritize finding an ideal location with regard to flow more so than lighting. Being such a fleshy coral you donÕt want to give it too much flow to the point that the skeleton starts to poke through the flesh. It can absolutely happen if the Acanthophyllia is getting hit continuously by a strong laminar flow.

As a general recommendation, I would keep an Acanthophyllia in a low to medium flow area and preferably one with variable flow patterns so one side of the coral doesnÕt get hit constantly. Normally I would be concerned about a coral placed on the bottom collecting detritus, but that is more of an issue with small polyp stony corals or large polyp stony corals that grow into a bowl-like shape. Acanthophyllia donÕt have any difficulty shrugging off detritus that settles on them so they can be kept in lower flow than most without issue.

The lower flow also makes it much easier to feed.

If you enjoy spot feeding your corals, you are in for a treat. Acanthophyllia exhibit one of the most dramatic feeding displays when it opens up. They practically turn themselves inside out to completely transform into a giant seafood receptacle.

They can be fed a variety of foods, so I wouldnÕt overthink it too much when selecting something to give them. LPS pellets or full sized krill would work fine. WeÕve even fed them larger items like silversides in the past.

What is kind of strange is how Acanthophyllia reacts to different food. One behavior IÕve seen is that it reacts the most enthusiastically to really small planktonic foods especially frozen rotifers. The colony opens way up but it is hard to tell if it is actually eating anything. I have a feeling that they are taking it in through their mucus coat it is just that their tentacles are not engaged in prey capture during that time.

Once it is fed larger chunkier food though it actively takes them in.

Another thing you can do in terms of feeding that isn't completely necessary, but will help keep your corals on the healthier side, is to feed them amino acids as well

Amino Acids are simple organic compounds that play a major role in building proteins as well as other biological functions at the cellular level. There are a little over 20 different types of amino acids. Most of them can be synthesized by the organism but some cannot be and must be taken in by feeding. Those amino acids are termed essential amino acids and they vary from species to species. Corals regularly take in available amino acids from the water column so it is easy to provide them with adequate quantities by broadcast feeding an amino acid solution. They are available from any number of commercially available reef supplement manufacturers. This may be the easiest way to feed your corals because as long as amino acids are bioavailable in the water column, the corals will soak them up.

Ê

Name: Acanthophyllia Temperature: 24-26C Flow: low-mid PAR: 50-150 Water parameters: Nitrate 5-20 mg/l, Phosphate 0,05-0,15 mg/l Feeding: Feeding is desired. Care level: Easy/Moderated Acanthophyllia are a large polyp stony coral often referred to as a donut or meat coral. They are similar in appearance to Scolymia/Homophyllia or Cynarina in that they are a single polyp, round in shape, and often times come in some dazzling colors and patterns. Seven years ago, I did a video on this coral and the title was something like ÒAcanthophyllia are an underrated LPS.Ó These days that could not be further from the truth. Nowadays, Acanthophyllia are highly desired among collectors of large polyp stony corals and I would go as far as to say that they are the absolute pinnacle for those looking for that signature show piece. The obvious downside to that level of demand is the price point for these guys. They are some of the most expensive corals in the industry. Luckily despite the prices, Acanthophyllia tend to be one of the more hardy corals out there. There are some corals that are notoriously sensitive and it is always a scare to drop serious money into a coral that is known to be challenging. Acanthophyllia are the opposite end of the spectrum. They can be housed in a wide range of tank conditions and can handle a modest degree of neglect. You really canÕt say that about a high end Acropora for example. The only thing I would mention about its hardiness is when it comes to shipping this coral. Shipping is always a stressful event for any coral but it can be particularly damaging for Acanthophyllia. Under all that flesh is one of the spikiest skeletons IÕve seen on any coral. This is troublesome for two reasons, the first is it can poke through shipping bags thus causing leaks and if you are shipping in cold weather, the leaking water can deactivate the heating packs in the box. Big yikes. So when it comes to packing these guys we donÕt skimp on the bags. I know IÕve used up to four giant 3-mil bags to send them out. The second problem with their spiky skeleton is that they can damage their skin during transit. Evan assuming they donÕt punch through the bag as they roll around, the spikes skeleton does poke through their skin. Like I said though, it is a good thing this coral is pretty tough because it does not take long for the coral to settle into an established reef aquarium and heal over that damage. Location Acanthophyllia are found throughout Indonesia and Australia. The specimens from Australia are predominantly that greenish blue mint-chocolate chip appearance. The specimens from Indonesia are mostly red and blue, but there are rare color variants that are all the colors of the rainbow. Those are the most desirable. Depending on the colors high end collectors are willing to pay well into the four figures, and occasionally I see a truly stunning piece that I can imagine someone spending a fortune on. Part of the reason for their scarcity is their availability in some countries. Right around the time of the Indonesian export ban in 2018, there were changes in what corals could be sent where and from what I understand Acanthophyllia was one of the most restricted corals once things opened back up. Here in the US they are still being brought in, but the prices are much higher than before. As for the future of the imports and exports for this coral, that remains unclear. The other aspect affecting its price is the fact that there are no good aquacultured sources for Acanthophyllia. They cannot be cut and sexual reproduction hasnÕt been accomplished on a commercial scale. Hopefully that changes in the future! That would be game changing, but we are talking about a monumental challenge given the difficulty associated with sexual reproduction on the commercial scale and the incredible slow growth of this coral. ThatÕs a little bit of background on Acanthophyllia. LetÕs now talk about their care requirements starting with lighting and placement. Lighting We primarily keep Acanthophyllia in low to medium light intensity here at Tidal Gardens which is around 50 to 100 PAR. We have kept them in higher lighting but they did not appear to appreciate it and were always at risk of bleaching out. If you have a colony of Acanthophyllia and want to experiment with higher light, remember that it can be a risk, so be prepared to move it into a shadier region of the tank at the first signs of trouble. As for placement, almost every tank I see these corals in keeps them at the bottom of the tank regardless of whether it has a substrate or bare bottom. They settle in nicely down there are when they are happy will extend nicely and take on that ChiliÕs lava cake appearance. I suppose there isnÕt a good reason that they couldnÕt be put up on a rock scape, but it is much less common. Perhaps the thinking is that higher up on the rock scape would expose the coral to more light and more flow which might not be the best combination for this coral. One other thing about placement to consider is to consider how much it will spread out once it settles into your reef tank. Acanthophyllia do not grow fast AT ALL, but they can swell many times larger than their skeleton so you want to avoid a situation where this coral reaches out and covers its neighbors. Water Flow LetÕs move on to water flow. We touched on it briefly in regards to placement, but I would prioritize finding an ideal location with regard to flow more so than lighting. Being such a fleshy coral you donÕt want to give it too much flow to the point that the skeleton starts to poke through the flesh. It can absolutely happen if the Acanthophyllia is getting hit continuously by a strong laminar flow. As a general recommendation, I would keep an Acanthophyllia in a low to medium flow area and preferably one with variable flow patterns so one side of the coral doesnÕt get hit constantly. Normally I would be concerned about a coral placed on the bottom collecting detritus, but that is more of an issue with small polyp stony corals or large polyp stony corals that grow into a bowl-like shape. Acanthophyllia donÕt have any difficulty shrugging off detritus that settles on them so they can be kept in lower flow than most without issue. The lower flow also makes it much easier to feed. Feeding If you enjoy spot feeding your corals, you are in for a treat. Acanthophyllia exhibit one of the most dramatic feeding displays when it opens up. They practically turn themselves inside out to completely transform into a giant seafood receptacle. They can be fed a variety of foods, so I wouldnÕt overthink it too much when selecting something to give them. LPS pellets or full sized krill would work fine. WeÕve even fed them larger items like silversides in the past. What is kind of strange is how Acanthophyllia reacts to different food. One behavior IÕve seen is that it reacts the most enthusiastically to really small planktonic foods especially frozen rotifers. The colony opens way up but it is hard to tell if it is actually eating anything. I have a feeling that they are taking it in through their mucus coat it is just that their tentacles are not engaged in prey capture during that time. Once it is fed larger chunkier food though it actively takes them in. Another thing you can do in terms of feeding that isn't completely necessary, but will help keep your corals on the healthier side, is to feed them amino acids as well Amino Acids are simple organic compounds that play a major role in building proteins as well as other biological functions at the cellular level. There are a little over 20 different types of amino acids. Most of them can be synthesized by the organism but some cannot be and must be taken in by feeding. Those amino acids are termed essential amino acids and they vary from species to species. Corals regularly take in available amino acids from the water column so it is easy to provide them with adequate quantities by broadcast feeding an amino acid solution. They are available from any number of commercially available reef supplement manufacturers. This may be the easiest way to feed your corals because as long as amino acids are bioavailable in the water column, the corals will soak them up. Ê

€2.499,00€1.999,00

SKU:

Acanthophyllia are a large polyp stony coral often referred to as a donut or meat coral. They are similar in appearance to Scolymia/Homophyllia or Cynarina in that they are a single polyp, round in shape, and often times come in some dazzling colors and patterns.

Seven years ago, I did a video on this coral and the title was something like ÒAcanthophyllia are an underrated LPS.Ó These days that could not be further from the truth. Nowadays, Acanthophyllia are highly desired among collectors of large polyp stony corals and I would go as far as to say that they are the absolute pinnacle for those looking for that signature show piece.

The obvious downside to that level of demand is the price point for these guys. They are some of the most expensive corals in the industry.

Luckily despite the prices, Acanthophyllia tend to be one of the more hardy corals out there. There are some corals that are notoriously sensitive and it is always a scare to drop serious money into a coral that is known to be challenging. Acanthophyllia are the opposite end of the spectrum. They can be housed in a wide range of tank conditions and can handle a modest degree of neglect. You really canÕt say that about a high end Acropora for example.

The only thing I would mention about its hardiness is when it comes to shipping this coral. Shipping is always a stressful event for any coral but it can be particularly damaging for Acanthophyllia. Under all that flesh is one of the spikiest skeletons IÕve seen on any coral. This is troublesome for two reasons, the first is it can poke through shipping bags thus causing leaks and if you are shipping in cold weather, the leaking water can deactivate the heating packs in the box. Big yikes. So when it comes to packing these guys we donÕt skimp on the bags. I know IÕve used up to four giant 3-mil bags to send them out.

The second problem with their spiky skeleton is that they can damage their skin during transit. Evan assuming they donÕt punch through the bag as they roll around, the spikes skeleton does poke through their skin. Like I said though, it is a good thing this coral is pretty tough because it does not take long for the coral to settle into an established reef aquarium and heal over that damage.

Acanthophyllia are found throughout Indonesia and Australia. The specimens from Australia are predominantly that greenish blue mint-chocolate chip appearance. The specimens from Indonesia are mostly red and blue, but there are rare color variants that are all the colors of the rainbow. Those are the most desirable.

Depending on the colors high end collectors are willing to pay well into the four figures, and occasionally I see a truly stunning piece that I can imagine someone spending a fortune on. Part of the reason for their scarcity is their availability in some countries. Right around the time of the Indonesian export ban in 2018, there were changes in what corals could be sent where and from what I understand Acanthophyllia was one of the most restricted corals once things opened back up.

Here in the US they are still being brought in, but the prices are much higher than before. As for the future of the imports and exports for this coral, that remains unclear.

The other aspect affecting its price is the fact that there are no good aquacultured sources for Acanthophyllia. They cannot be cut and sexual reproduction hasnÕt been accomplished on a commercial scale. Hopefully that changes in the future! That would be game changing, but we are talking about a monumental challenge given the difficulty associated with sexual reproduction on the commercial scale and the incredible slow growth of this coral.

ThatÕs a little bit of background on Acanthophyllia. LetÕs now talk about their care requirements starting with lighting and placement.

We primarily keep Acanthophyllia in low to medium light intensity here at Tidal Gardens which is around 50 to 100 PAR. We have kept them in higher lighting but they did not appear to appreciate it and were always at risk of bleaching out. If you have a colony of Acanthophyllia and want to experiment with higher light, remember that it can be a risk, so be prepared to move it into a shadier region of the tank at the first signs of trouble.

As for placement, almost every tank I see these corals in keeps them at the bottom of the tank regardless of whether it has a substrate or bare bottom. They settle in nicely down there are when they are happy will extend nicely and take on that ChiliÕs lava cake appearance. I suppose there isnÕt a good reason that they couldnÕt be put up on a rock scape, but it is much less common. Perhaps the thinking is that higher up on the rock scape would expose the coral to more light and more flow which might not be the best combination for this coral.

One other thing about placement to consider is to consider how much it will spread out once it settles into your reef tank. Acanthophyllia do not grow fast AT ALL, but they can swell many times larger than their skeleton so you want to avoid a situation where this coral reaches out and covers its neighbors.

LetÕs move on to water flow. We touched on it briefly in regards to placement, but I would prioritize finding an ideal location with regard to flow more so than lighting. Being such a fleshy coral you donÕt want to give it too much flow to the point that the skeleton starts to poke through the flesh. It can absolutely happen if the Acanthophyllia is getting hit continuously by a strong laminar flow.

As a general recommendation, I would keep an Acanthophyllia in a low to medium flow area and preferably one with variable flow patterns so one side of the coral doesnÕt get hit constantly. Normally I would be concerned about a coral placed on the bottom collecting detritus, but that is more of an issue with small polyp stony corals or large polyp stony corals that grow into a bowl-like shape. Acanthophyllia donÕt have any difficulty shrugging off detritus that settles on them so they can be kept in lower flow than most without issue.

The lower flow also makes it much easier to feed.

If you enjoy spot feeding your corals, you are in for a treat. Acanthophyllia exhibit one of the most dramatic feeding displays when it opens up. They practically turn themselves inside out to completely transform into a giant seafood receptacle.

They can be fed a variety of foods, so I wouldnÕt overthink it too much when selecting something to give them. LPS pellets or full sized krill would work fine. WeÕve even fed them larger items like silversides in the past.

What is kind of strange is how Acanthophyllia reacts to different food. One behavior IÕve seen is that it reacts the most enthusiastically to really small planktonic foods especially frozen rotifers. The colony opens way up but it is hard to tell if it is actually eating anything. I have a feeling that they are taking it in through their mucus coat it is just that their tentacles are not engaged in prey capture during that time.

Once it is fed larger chunkier food though it actively takes them in.

Another thing you can do in terms of feeding that isn't completely necessary, but will help keep your corals on the healthier side, is to feed them amino acids as well